Why government run shared services often fail

In this blog and the next blog I want to share some of my thoughts on government agencies using shared services. More specifically: why do they often function so cumbersome that they make it into the newspapers.

What makes shared services within government different

Centralization of IT or processes like finance, HR administration offers the ability to rationalize and standardize processes, allowing for lower cost, more consistent quality level and faster decision making. As voters expect their ministries and other government agencies to eat as little as their tax money as possible (especially in these times of economic hardship in the US and Europe), is sharing resources and processes a useful vehicle to achieve that goal.

As a result many ambitious objectives have been defined by high ranking government officials. These government officials did however not always realize that ‘sharing resources and processes’ also effects their power base. Where they use to rule their little kingdom, they now have to talk to other little kings about a common approach. Sharing that hard earned throne is however not something that is part of the standard government culture.

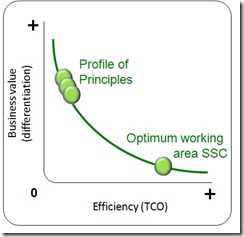

A culture which is shaped by the political context they operate in and often hundreds of years of semi-independency. The political context is influenced by objectives and tasks from various stakeholders. Stakeholders like voters, politicians and government workers higher up in the food chain. To make things even more complex, the needs of these stakeholders are not static, they change. This results in a very complex and dynamic environment. And complexity and especially dynamics are not friends of a shared services. Shared service centers (SSC) have their optimal working area in a relatively static environment as this allows for standardization and functional pooling of resources.

When a SSC is created this ‘tension’ between demand (the ‘business’) and supply (‘supply’) remains under water as creating an organizational structure and filling it with people does not actually change anything yet. All the little kingdoms are still as they were before. The actual change starts when the first processes have to be transferred or the first shared project is initiated. Then all of a sudden all the differences surface. Differences which are often considered insignificant by somebody working in a commercial company, but can result in years of trench wars within government agencies.

Splits between demand and supply

The SSC finds itself now in an impossible position. The Principles that initiated the shared service center and gave it the objective to cut cost, are the same people that prevent it achieving that objective. The result is a nice negative feedback loop. In order to keep the Principles ‘on board’ the SSC creates a lot of exceptions and customizations. This increases however the cost level (and thus financial charge for the Principle), increasing the frustration and need for the SSC to be even more willing to allow for customizations next time round.

In other words: the difference in optimum working area of the SSC and the dynamics of its Principles often leads to considerable tension between supply and demand. The result are budget overruns and missed timelines. In most cases both parties acknowledge that there is an issue/mismatch, but the next projects ends the same way is the culture turns out to be stronger than the rational dictation change. At the end of the day, the king wants to remain king.

In a follow up blog I will share two approaches to ease the tension and bring demand and supply closer together.

Comments

Post a Comment